Mathematics homework in 2023 often has parents scratching their heads and admitting defeat. Oregon State University senior Madison Collins knows that feeling all too well.

At the dinner table growing up she disagreed with her parents on how to break up numbers for addition and multiplication problems. “My mother had different methods of math that she learned,” she said. “I went, ‘Mom, that’s not how my teacher told me to do it.’” Luckily for Collins, math came naturally, and her parents tried to keep her on her toes with new academic topics.

Until one day, she surpassed her father, an important figure in her life who encourages and challenges her academically.

“It was fun when I was talking to him about math content and he said, ‘I have no idea what you’re talking about.’” That’s when Collins realized, after all these years, she finally surpassed her father at a higher level of mathematics.

Modernizing the education process

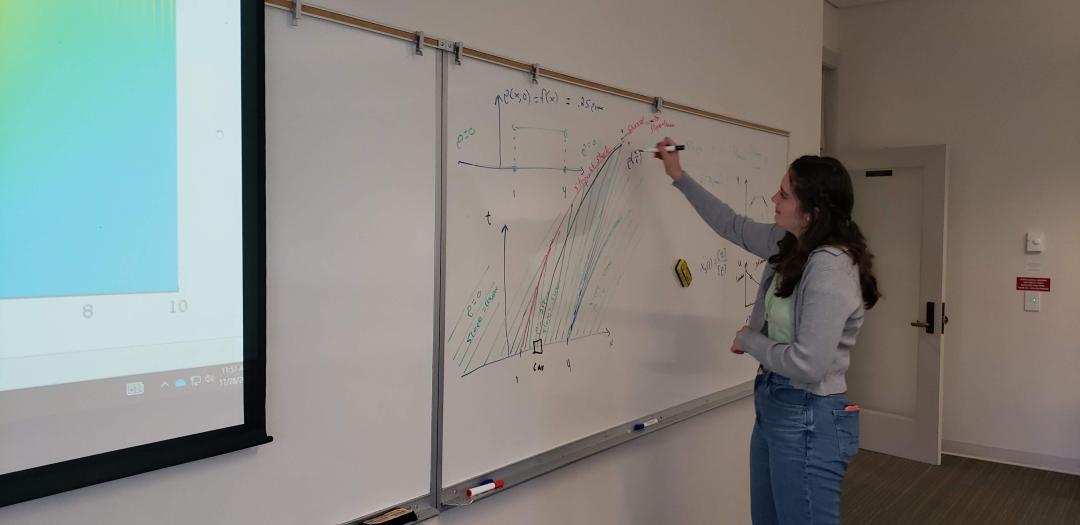

A third-year student graduating with a bachelor's degree in mathematics with the mathematical biology option and a minor in chemistry, Collins plans to hit the ground running by starting her master's degree in math education at Oregon State in fall 2023. Even though 1+2 will always be equal to 3, Collins strives to teach math differently so that students can learn better and discover something new along the way.

“I want to help students from multiple backgrounds see that learning math and succeeding in a college math course is possible for them. I want to be able to communicate math well to students so they can learn the content and gain confidence in their mathematical abilities,” she said. “In college, a lot more students don’t feel like they can connect to the teachers personally, so I definitely want to try to build up the community in that way while teaching.”

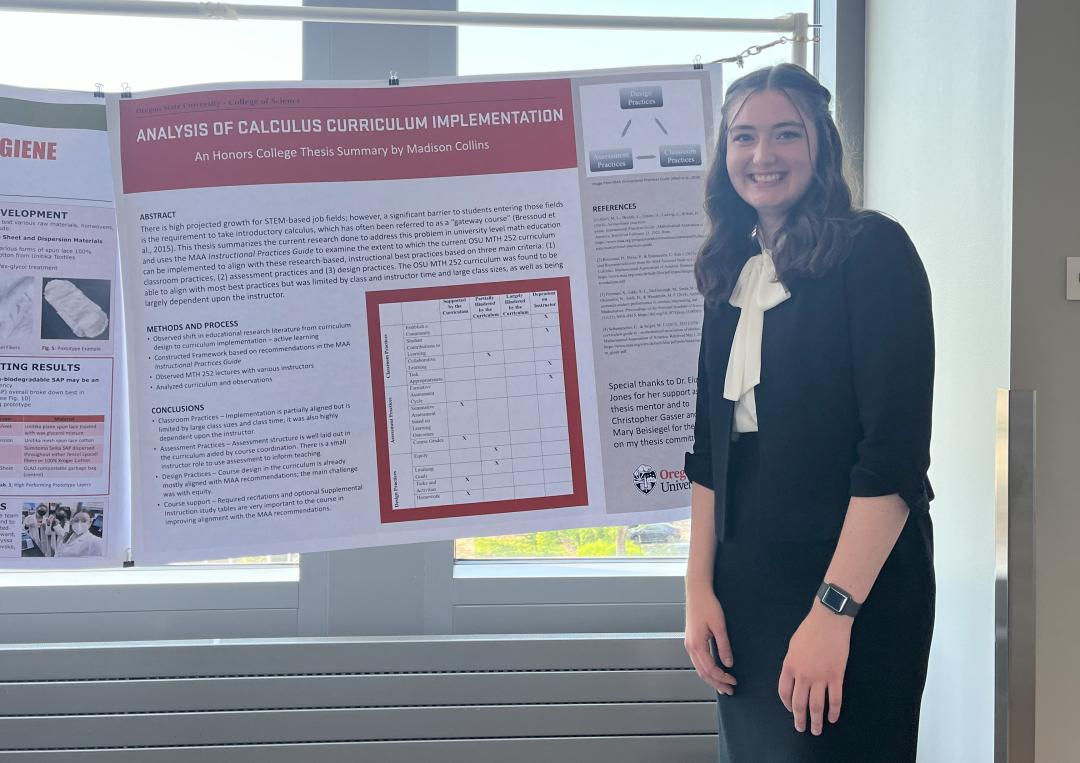

Collins has already started analyzing how the college-level calculus curriculum is being taught in the classroom for her honors thesis. Her curriculum curiosity dates back to the table in her childhood kitchen.

Whenever she and her sister got stuck on a math problem, her parents paused dinner to get them back on track. Sometimes, this meant her parents teaching them ‘weird’ and ‘wacky’ methods that aren’t taught in school anymore. To Collins, this is a typical part of the education process.

“While parents being able to help kids with homework is really important, a lot of research has gone into improving education with new teaching strategies and ways of communicating certain ideas,” she said. “New advances are being made in math education theory all the time so the content delivery is changing. It is unrealistic not to change math to keep up with new understandings of concepts. With that said, many math curricula, especially calculus, have remained largely unchanged for decades.”

When Collins entered high school, she loved to ‘move pieces around’ to solve puzzle-like math problems in her calculus courses. Outside of the classroom, she chose to do sports instead of working a job, a choice that greatly impacts how she views the education experience. Joining the cross country, swimming and track teams helped her grow and prepare for the rigor of college courses early on.

Even though she didn’t continue sports at Oregon State, Collins kept running on her own during college. She competed in the April 2023 half marathon in Corvallis alongside her boyfriend while her uncle and mother ran the 5k.

Training for 13.1 miles, spending time with her family and developing a thesis in the same term required a work-hard-play-hard attitude. Especially when that workload also included tutoring.